STEM Problems Students Can Really Address

Excerpted from “Ten Think-Abouts for Preparing to Teach STEM,” Chapter 4, STEM by Design by Anne Jolly (Routledge 2017). All Rights Reserved.

Think-About #3:

What Kinds of Problems Can My Students Realistically Address?

Problem-solving is fundamental to STEM. But coming up with real-world engineering challenges for students to solve can be tricky. Here are some ideas about locating problem possibilities.

◆ Encourage student-generated problems. These are obviously ideal for creating student enthusiasm and engagement. Adolescent students love to make learning about “me.” Give them as much input as possible into problems they want to solve, within constraints dictated by the curriculum.

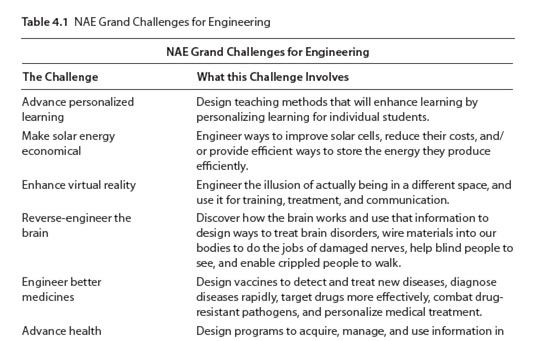

◆Check out 14 Grand Challenges for Engineering. In the 2008 National Academy of Engineering Grand Challenges for Engineering report, the NAE identified 14 broad categories of problems that we as a nation must be prepared to solve in this century. Mull over the list of real-world problems. Your students might be interested in designing model solutions related to some of these. Some Grand Challenges that I think might inspire middle school STEM students include solar energy, clean water, health care (including food shortage and disease and accessibility issues), and urban infrastructure (including transportation systems and visually appealing bridges and municipal structures).

Sample items from Table 4.1 in STEM by Design (Routledge, 2017)

◆ Do an Internet STEM Lesson search. Simply typing “real-world problems” into a search engine can bring up a host of possible sites that you can sift through for ideas. Of course, everything labeled “STEM” is not necessarily a true STEM lesson. To narrow your search you might detour over to the Resources section in the Appendices and examine some sites mentioned under “STEM Lessons.” Be sure the check out the Link Engineering website for great insights into good STEM lessons as well as information about engineering design.

◆ Keep the problem do-able. Whether your students identify a problem to solve or you choose the engineering challenge, be sure to keep it do-able. Consider (1) what students have already learned that can help with solving this problem, and (2) the resources available for the challenge. Engineering solutions for a problem involving clean energy (wind turbines, solar cells, etc.) might be quite realistic. Tackling a problem involving interplanetary travel—not so much.

◆ Line up a resource support group. Your science and technology labs may be well-equipped to allow students access to digital tools, measuring devices, and other equipment. Realistically, though, you will still find times when supplies needed for a STEM lesson will include items such as wood, wire, cardboard, tape, string, tongue depressors, paper and plastic cups, plastic spoons, foam board, and so on.

Lining up some business partners to help with STEM supplies can solve your resource problem. For example, doctors, dentists, and hospitals may donate supplies such as surgical gloves and tongue depressors. Some businesses may donate office-type supplies; others may donate money. Parents and PTA groups are generally more than willing to send paper towels, paper plates, cups, and spoons, and other household items you may need. I found that colleges and universities would often donate perfectly usable science equipment that they were replacing. Our local police station donated some triple-beam balances. Be creative in beginning to assemble a resource support group.

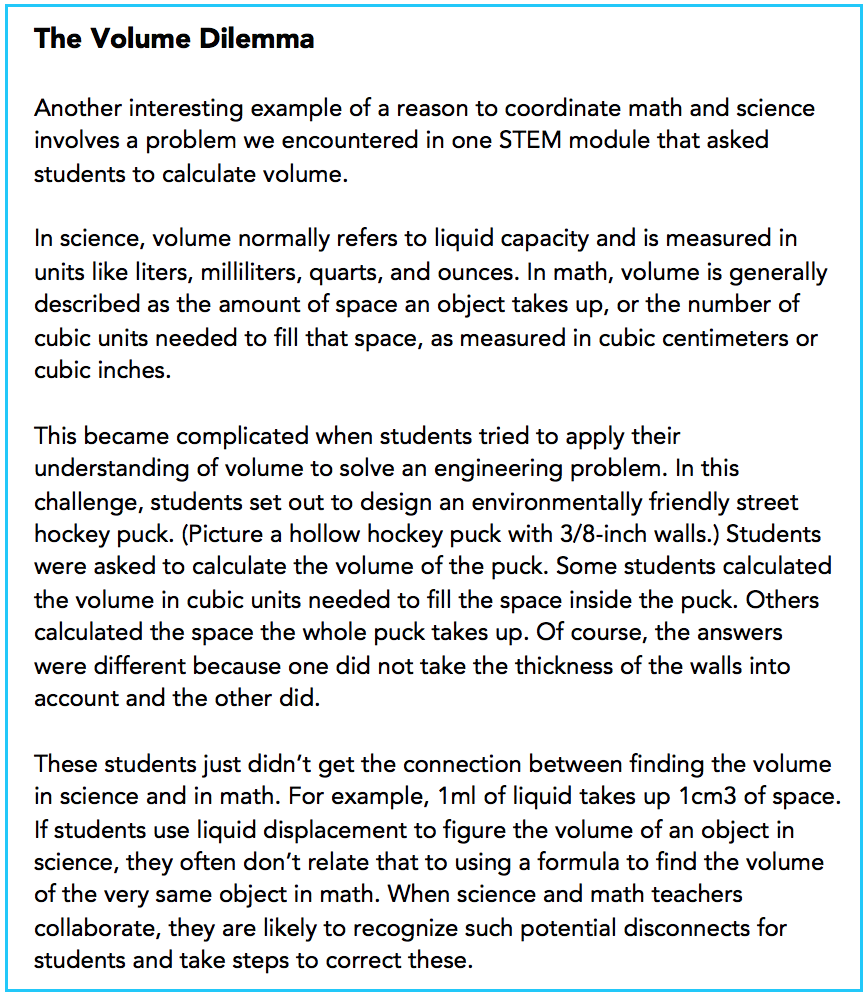

◆ Be sure to get comfortable with both the math and the science content your students will use in each challenge. If you teach only science, or only math, be sure you collaborate with a teacher in the other field. In the language of math and science, terms sometimes mean slightly different things. For example, the term “factor” when used in science might refer to something that contributes to a result, such as a catalyst in a chemical reaction. In mathematics, a factor is a number (or algebraic expression) that is multiplied together with another number to produce a given product. You want to be aware of possible inconsistencies in terminology and be sure you are using the correct “teacher talk” in discussing science and math content with students.

I love STEM.

Nice post.

I agree that teachers need to be comfortable with the relevant content. We emphasize the need for consistent language in all our classes as well at our school. How do you go about covering the necessary content if the students come up with the topic?